Central Bank Independence and Inflation

Why is Independence Important? Is the Fed Really Independent When it Faces Pressure?

Disclaimer: I am not a trained economist, and am still in my formative stage of economics education. These are based on my research and are designed to invite discussion rather than prove a new economic theory. Criticism is welcome through either the comment section or my email: Eridpnc@gmail.com

Summary

Part One: Central bank independence prevents inflation from spiraling out of control by serving as a reliable anchor for inflation expectations. The interest rate is a tool that signals the central bank’s resolve to hurt the economy to stabilize inflation, which greatly reduces compliance costs.

Part Two: Some argue that central banks are not independent, since their actions are inevitably influenced by direct congressional modification and indirect political pressure.

Part Three: This position is incorrect. While technically surmountable, the political separation between the Fed and political branches nevertheless serves as a political buffer. To subvert the Fed, the government requires a public campaign and shift of political expectations, which is difficult enough to deter interference.

The Fed does has the will and means of bringing down inflation, even if it does harm the economy.

Part One: Why Independence?

Imagine you’re stuck in traffic. You’re on a large highway, with cars lined up as far as the eye can see. Three miles away, a light turns green. In a world of perfect coordination, every car moves at the same time, bumper to bumper. In the real world, it takes many minutes for you to start moving again.

The credibility of the central bank works the same way. If everyone believes the Fed will reach its inflation target, then success is easy and cheap. This is because every time someone makes a transaction with the expectation of 2% inflation, they actively contribute to that goal.

However, if someone doesn’t believe the target, they actively make the adjustment process longer and more costly. For example, if someone predicts the inflation rate will be higher than expected, they will spend a larger portion of their money now, demand higher wages, or raise prices if they are a business owner. All of these actions increase the aggregate price level.

Of course, inflation is literally constrained by the amount of money in the economy. But this constraint is unpredictable and only kicks in after the economy has sustained inflation for a very long time.

Low and stable inflation is a good goal for central banks to pursue. The purpose of all currency is to reduce uncertainty, which volatile inflation prevents. When there is high inflation, prices change quickly and unpredictably, which makes people more doubtful about spending money. Long-term contracts and loans become more difficult to make because of this, and more success and failure in the economy is determined by random fluctuations in currency rather than true value created. People become less certain about their level of wealth, lowering their quality of decision-making.

Additionally, inflation correlates with overspending and overuse of resources, as prices increasing quickly means resourcesare being depleted at an unsustainable rate. All of this harms future growth.

By increasing interest rates, the central bank signals that it is willing to harm the economy in the short-term to reduceinflation. Interest rates incentivize saving, which reigns spending in. However, the direct effect of interest rates is small in comparison to the signaling effect.

A study from the Federal Reserve models three different scenarios:

Credible Model—Everyone unquestionably believes the central bank’s inflation target one quarter after the target is released. In other words, perfect coordination.

Public Model—This model is used by the Federal Reserve. It models inflation as 90% from long-term inflation expectations, 5% from the inflation target, and 5% from past inflation.

Accelerationist Model—Inflation is entirely due to economic incentives and past inflation. This is effectively a world where the central bank did not target inflation or lacked all credibility, causing actors to ignore the signaling effect

The study computes the sacrifice ratio, which is the amount of economic harm required to tame inflation. It is calculated as follows:

-(Average Percent of Total Economic Output Lost/Change in Inflation Rate)

For example, if a country losesan average of 20% of its GDP over a time period, but disinflates by 10%, there is a sacrifice ratio of 2. A higher sacrifice ratio means that the cost of bringing inflation down is larger.

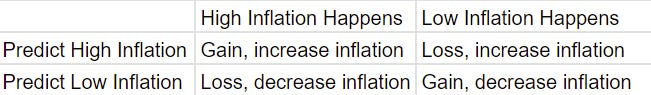

Figure 1: Inflation Under Various Levels of Credibility

Note: I am using the MCAP data1

In the credible model, the total negative economic effect required to cause disinflation is about 20 times less than the accelerationist model. Without the signaling effect, it takes a loss of 26.9% of output to cause 1% disinflation.

So, the first job of the central bank is to convince the public. By setting a target of inflation, it is able to keep long-term expectations close to the same number, enabling all actors in the economy to coordinate spending. This speeds up recovery from high inflation, reducing negative effects.

Part Two: Arguments Against Independence

There are three arguments2 about why independence doesn’t work in practice:

The Fed has no legal independence. Congress created the Fed to serve congressional purposes. Congresscan change the Fed’s authority and goals at any time, and have done so many times in history.

The Fed undergoes strong informal political pressure from both sides. Everything it does is inevitably made political because of how big the effects are. It has to keep its popularity with Congress and the public in order to prevent its authority from being diminished.

The Fed is structurally biased. The president has every incentive to appoint someone who shares their ideas about the economy, which prevents objective policy from being implemented.

Part Three: Answering Arguments Against Independence

Suppose there was a small island a few miles off the coast of California. It has no military, a few hundred citizens, and hundreds billions of dollars worth of natural resources. It claims to be a different country, and is a member of nearly every alliance the United States is in. It allows the United States to harvest its resources, but only under very strict regulations believed to be best for preserving these resources and achievingthe maximum long-term benefit.

What would the United States do? A cynic declares that the United States would simply capture this island. There’s plenty of political pressure for this action, especially when the economy badly needs these resources. However, invading would require contravening every treaty, alliance, and international agreement the United States follows. It would draw condemnation from organizations both in and out of the US. If a politician tries to unduly influence the agreement, they’re instead shamed.

This situation is the same as what the Fed faces. While the Fed has no formal authority to resist Congress, it nevertheless is well-insulated from pressure.

Certainly, there are times when the Fed is forcefully reformed. The point of independence isn’t to prevent change, only make it painful. Congress cannot simply pass a bill to reduceinterest rates. Instead, they must propose reworking the nation’s central bank to give themselves more power, usually against the favor of economists. Reforming the Fed requires overwhelming, bipartisan support, preventing biased decision-making.

There are few regulations over American history that explicitly target the Fed. Here’s a simplified list of the effects of all major regulations:

Figure 2: History of Major Congressional Fed Changes

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

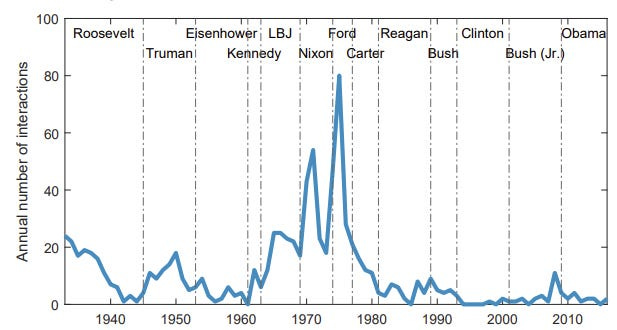

There are a few times when this process is bypassed. A case study on president Nixon’s pressure against Arthur Burns (the Fed chair at the time) examines this relationship. Nixon, while gearing up for re-election, harassed Burns for a year with concerns about the money supply, meeting more than 100 times. For comparison, the average is only three. It finds that Nixon’s pressure on the Fed caused it to expand the money supply, hurting its credibility and making inflation difficult to fight for the next decade.

The study continued by analyzing how pressure in the form of president-Fed interactions across American history influenced inflation. It found that interactions had strong predictive value even accounting for other variables such as investment and past growth.

This is what the model predicted after an increase of 10 president-fed interactions in one quarter, a decently large shock:

Figure 3: Quarters After Shock (bottom) and Increase in Predicted Inflation Rate (left)

Since the study randomized shocks, the red line is the median prediction, while the red shading are predictions within the middle 68% range. It found a clear, statistically significant increase of about 5% in the price level after 18 quarters, which is about a 1% increase in the inflation rate over 4.5 years.

It’s clear that the Fed wasn’t independent that year. But this example is an exception to the norm. Markets were surprised by Nixon’s decision and reacted adversely by predicting a higher level of inflation.

Since Nixon, president-Fed interactions have considerably decreased3, shown here:

Figure 4: President-Fed Interactions per Year (left) and Time (bottom)

Congressional pressure on the other hand is relatively common, although less intense. Usually, it’s in the form of Congresspeople writing letters to the Fed requesting stimulus. The Fed does have a genuine choice on whether to listen, and almost always refuses.

Here are notable events from the past few chairs:

Paul Volcker (1979-1987)—Famously raised interest rates so high that the economy had a recession for more than a year. He also publicly announced that he would be willing to allow interest rates to change more than any time in history.

Figure 5: Interest Rates During Volcker’s Regime in Between Black Brackets

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

Alan Greenspan (1987-2006)—Resisted pressure from president Bush (both junior and senior) to cut rates despite being a lifelong republican.

Ben Bernake (2006-2014)—Created countless lending and quantitative easing programs after the 2008 recession despite criticism from both sides of Congress and the public.

Janet Yellen (2014-2018)—Raised rates extremely slowly during high inflation in 2014, facing pressure to raise rates faster from Congress due to fears that inflation would get worse.

Jerome Powell (2018-Now)—Resisted lots of pressure from president Trump who tweeted asking him to lower rates, repeatedly insulted him, and contemplated firing him not doing so.

Figure 6: Trump Tweet Following Powell’s Decision Not to Lower Rates

Even when pressured, the vast majority of chairs stayed their course and did what they thought was best. Presidents of both sides have been willing4 to cross political boundaries, with both sides appointing Greenspan, Bernake, and Powell

This ability to harm the short-term economy is unique to the central bank. Congress, meanwhile, has not increased the income tax since 1993, and has since passed four major cuts5. The short terms in Congress and the White House exposes politicians to constant pressure from voters, preventing any painful decisions.

To minimize the cost of disinflation, the public must be actively engaged and informed of recent developments. There must be an independent entity that is capable of harming the economy quickly and decisively.

Conclusion

Inflation is based on expectations. While it can be literally corrected through interest rates, the cost of this is extremely high. One solution to this is to establish a central bank with an inflation target. If markets believe the central bank, then inflation will come down quickly and without a substantial cost to the economy. If not, then inflation becomes far more costly to fight.

Some argue that central bank independence is fake, as congress has the legal power to adjust Fed policy and presidents can bypass rules by pressuring the Fed to reduce rates.

These arguments are wrong. The Fed does have the willingness and power to substantially harm the economy. Even if politicians can take this power away, markets believe they won’t in the near future, which allows them to keep stable and low expectations of inflation.

Model-Consistent Asset Prices (MCAP) assumes that actors in financial markets buy and sell with respect to financial policy, while wage and price expectations lag behind and adjust based on economic incentives. Model-Consistent-Expectations (MCE) assumes that wages and price expectations are perfectly flexible, which is generally considered unrealistic.

There is also a lot of academic debate about whether the Fed goes too far outside of its dual mandate. This is a totally separate academic rabbit hole, but if you’re interested, here is some reading:

here is an article that looks through potential small-scale approaches for the Fed

here is an article that breaks down the problems with trying to expand outside the dual mandate

here is a study of central bank activism in climate change that advocates for more involvement.

Trump and Biden administration omitted because the data were not released during the study’s publication. This is unfortunate because I will show later that Trump is the notable exception

Trump was forced to after his other nominees, Herman Cain, Stephen Moore, and Judy Shelton were considered too radical and blocked from appointment.

It is a pleasure to read this paper. I like your solid analysis based on historical facts. This gives me a new perspective on Fed's decision, esp. during this "painful" "high" interest rate couple of years.